Westmeath

WESTMEATH (County of), an inland county of the province of LEINSTER, bounded on the east by the county of Meath; on the north, by those of Meath, Cavan, and Longford; on the west, by those of Longford and Roscommon ; and on the south, by the King’s county. It extends from 53º 18’ to 53º 47’ (N. Lat.), and from 6º 55’ to 7º 55’ (W. Lon.); comprising an area, according to the Ordnance survey, of 386,251 statute acres, of which 313,935 are cultivated land, 55,982 are unimproved mountain and bog, and 16,334 are under water. The population, in 1821, amounted to 128,819; and in 1831, to 136,872.

This county formed part of the kingdom of Meath when the island was divided into five provincial dynasties, and was then known by the name of Eircamhoin, or “the Western Division.” Its provincial assemblies were held at the hill of Usneagh, supposed by some to be the Laberus noticed by Ptolemy as one of the inland cities of Ireland. In 1153, the northern part of the county became the scene of contention between two sons of Dermod O’Brien, who terminated their strife by a bloody battle fought near Fore, in which Turlogh having obtained the victory, became master of his brother’s person and put out his eyes. The principal Irish families during this period were those of MacGeoghegan (chieftains of Moycashel),O’Mulbrenan or Brenan, O’Coffy, O’Mullady, O’Malone, O’Daly, O’Higgins, Magawly, Magan,O’Shannagh (afterwards changed to Fox), O’Finilan and O’Cuishin. The annals of the religious houses prove that this county suffered much during the period in which the island was exposed to the predatory incursions of the Danes; the town and abbey of Fore alone having been burnt nine times in the 10th and 11th centuries, either by the Danes or by the bordering Irish chieftains. After the settlement of the English in Leinster , the county formed part of the palatinate of Hugh de Lacy, who allotted it in large tracts to his principal followers, the most remarkable of whom were Petit, Tuite, Hussey, D’Alton, Delamare, Dillon, Nugent, Hope, Ware,Nangle, Ledewich, Geneville, Dardis, Gaynor, and Constantine. Subsequently, the families of Darcy, Johnes, Tyrrell, Fitzgerald, Owen, and Piers settled here at various periods previous to the Reformation. The ancient Irish were not at once exterminated by the new settlers: they made several attempts to recover their former position, in one of which, in 1329, MacGeoghegan, chieftain of Moycashel, defeated an English force under Lord Thomas le Botiller, who was killed in the action. Two years after the Irish were defeated in a battle near Finae by Sir Anthony Lucy, Lord Justice. Mortimer, Earl of March, who married Philippa, daughter and heiress of Lionel, Duke of Clarence, third son of Edward III., finding it necessary to conceal himself during the troubles that followed the deposition of Richard II., chose this county as his place of refuge, where he remained a long time in concealment. In 1468, Delamar, abbot ofTristernagh, was attainted by act of parliament for uniting with the Irish enemies and English rebels in an insurrection in which the town of Delvin was burnt. By an act of the 34th of Hen. VIII., the ancient palatinate of Meath was divided, the eastern portion retaining its former name and the western being distinguished by the appellation which it still retains. Longfordwas a portion of the latter division, until it was formed into a distinct county by Elizabeth. The plan for the insurrection of 1641 is said to have been concerted in the abbey of Multifarnham, in this county, as being conveniently situated in the centre of the island and a place of great resort for religious purposes, so that the assemblage of large numbers there at any particular time was less liable to suspicion: and in the subsequent war between William and James the county was the scene of several severe actions. So great was the change of property occasioned by the confiscations after these wars, that not one of the names of the persons who formed the previous Grand Juries are found on the modern lists.

The principal families who obtained grants of confiscated lands were those of Packenham, Wood, Cooke, Stoyte, Reynell, Winter, Levinge, Wilson, Judge, Rochfort, Handeock, Bonynge, Gay, Handy, Ogle, Middleton, Swift, Burtle, and St. George. Those of Smith, Fetherston, Chapman, O’Reilly, Purdon, Nagle, Blaquiere, and North obtained property by purchase or inheritance. Among the recent settlers, the family of Nagle alone claims from an ancient proprietor, having inherited in the female line from the MacGeoghegans. On the landing of the French at Kilcummin a rising took place in this county, in consequence of an erroneous report from the north: the peasantry first assembled at the hill of Skea, whence they proceeded to Lord Sunderlin’s park, but retired without committing any act of hostility. Afterwards they attacked and plundered Wilson’s Hospital, where there was a collection of arms, and having converted it into a barrack, kept possession of it until driven out by a detachment of the royal forces.

This county is partly in the diocese of Ardagh, but chiefly in that of Meath, and in the provinceof Armagh. For purposes of civil jurisdiction it is divided into the baronies of Brawney,Clonlonan, Corkaree, Delvin, Demifore, Farbill, Fartullagh, Kilkenny West, Moyashel andMagheradernan, Moycashel, Moygoish, and Rathconrath. It contains the market and assize town of Mulingar, part of the borough and market town of Athlone, the corporate and market town of Kilbeggan ; the market and post towns of Monte, Rathowen, Castletown-Delvin,Ballinacargy, and Clonmellon ; the market town of Collinstown ; and the post-towns ofCastlepollard, Kinnegad, Ballymore, Tyrrells-Pass, Killucan, Rochfort-Bridge, and Drumcree : the largest villages are Finae (which has a penny post), Coole, Castletown, and Rathconrath. It sent ten members to the Irish parliament, two for the county and two for each of the boroughs ofAthlone, Mullingar, Kilbeggan, and Fore, the last of which is now a small village ; since the Union it has returned three members to the Imperial parliament, two for the county, and one for the borough of Athlone, The county constituency, as registered up to the beginning of 1837, consists of 302 freeholders of £50, 146 of £20, and 1079 of £10 ; 13 leaseholders of £20, and 110 of £10; making a total of 1650 re-gistered voters. The election takes place at Mullingar. Westmeath is included in the Home Circuit: the assizes are held at Mulhingar, where the county court-house and gaol are situated ; general quarter sessions are held alternately at Mullingar and Moate, and at the latter place are a court- house and bridewell. The local government is vested in a lieutenant, 7 deputy-lieutenants, and 94 other magistrates. There are 47 constabulary police stations, having a force of 1 stipendiary magistrate, 1 sub-inspector, 6 chief officers, 50 constables, 222 men, and 9 horses. The district lunatic asylum is atMaryborough, the county infirmary at Mullingar, and the fever hospital at Castlepollard : there are dispensaries at Glasson, Bally nacarrig, Multifarnham, Street, Killucan, Kinnegad, Tyrrell’s-Pass, Moate, Kilbeggan, Athlone, Castletown-Delvin, Drumcree, Clonmellon, Milltown, andCastlepollard, supported by Grand Jury presentments and private subscriptions in equal proportions. The Grand Jury presentments for 1835 amounted to £23,296. 14. 8¼ .of which £15. 7. 0. was for the roads, bridges, &c., being the county charge ; £609. 0. 10½ . for the roads, bridges, &c., being the baronial charge ; £8837. 3. 4¼ for public buildings, charities, officers’ salaries, and incidents; £5618. 14.3¾ for the police, and £8216. 9. 1¾ for repayment of advances made by Government. In the military arrangements the county is included in the western district, of which Athlone is the headquarters, where there are two barracks, one for artillery and the other for infantry, which, with an infantry station at Mullingar, afford accommodation for 80 officers and 1806 non-commissioned officers and men, with 208 horses.

The surface of the county, though nowhere rising into tracts of considerable elevation, is much diversified by hill and dale, highly picturesque in many parts, and deficient in none of the essentials of rural beauty, but timber. In its scenery it ranks next after Kerry, Wicklow,Fermanagh and Waterford. None of the hills are so high as to be incapable of agricultural improvement. Knock Eyne and Knockross, on the shores of Lough Dereveragh, have on their sides much stunted oak and brushwood, the remains of ancient forests. The former of these hills is about 850 feet high. Benfore, near the village of Fore , is 760 feet high. The lakes are large, picturesque, and very numerous, mostly situated in the northern and central parts, the southern being flat and overspread with bog. The largest and most southern of the lakes isLough Innel or Ennel, now called also Belvidere lake: it is 1½ mile from Mullingar, and is studded with eight islands, the largest of which, called Fort Island, was garrisoned and used as a magazine by the Irish in the war of 1641, and was twice taken by the parliamentary forces, and ultimately retained by them till the Restoration. The names of the others are Shan Oge’s, Goose, Inchycroan, Cormorant, Cherry, Chapel and Green Island : the Brosna passes through it from north to south. To the north of this lake is Lough Hoyle, Foyle, Onel or Owel, in the very centre of the county; the land around it rises gently from its margin, and is fertile and richly planted. The only stream by which it is supplied is the Brosna. Two streams, called the Golden Arm and the Silver Arm, formerly flowed from it, one from each of its extremities: both have been dammed up, and the low grounds on the borders of the lake raised by embank ments so as to increase the body of Water contained in it, in order to render it the feeder of the summit level of the Royal Canal : this alteration has enlarged the surface of the Hoyle to an extent of 2400 acres. The lake has four islands, on one of which is an ancient chapel of rude masonry, with a burial-ground, much resorted to by pilgrims from distant parts; it afforded an asylum to many of the Protestants in the neighbouring country at the commencement of the war of 1641: the other islands are planted. Further north is Lough Dereveragh, a sheet of winding water of very irregular form, 11 miles long and 3 in its greatest breadth ; its waters discharge themselves through the lower Inny into Lough Iron, or Hiern, which is the most western lake in the county, and is likewise a long sheet of water, being a mile long and but ¼ of a mile broad, and very shallow : its banks are enriched with some fine scenery towards Baronstown andKilbixy ; from its northern extremity the Inny takes its course towards the county of Longford.Lough Lein, three miles to the east of Lough Dereveragh, is of an irregular oval form, two miles long and one broad : its waters are peculiarly clear, and remarkable for having no visible outlet, nor any inlet except a small stream which flows only in rainy seasons : it is surrounded on every side by high grounds, which on the north and south rise into lofty hills from the margin of the lake, and are clothed to their summits with rich verdure and flourishing plantations : there are four fertile and well, planted islands in the lake. In the west is Lough Seudy, a small but romantic sheet of water near the old fortress of Ballymore. Two miles north-east from Mullingar are the small lakes of Drin, Cullen and Clonshever ; Lough Drin supplies Lough Cullen, which, after flowing through a bog, falls into Lough Clonshever, whence the Brosna derives its supply since the waters of Lough Hoyle have been appropriated exclusively to the supply of the Royal Canal. Among the other smaller lakes scattered throughout the country, the principal areLough Maghan and the two lakes of Waterstown, near Athlone. The fine expansion of the river Shannon, called Lough Ree, may be considered as partially belonging to this county, as it forms the principal part of the western boundary between it and Roscommon : it is twenty miles long in its greatest length from Lanesborough to the neighbourhood of Athlone, and is adorned with several finely wooded islands : those adjoining Westmeath are Inchmore, containing 104 acres, once the site of a monastery built by St. Senanus; Hare island, containing 57 acres, and having the ruins of an abbey built by the Dillon family; Inchturk, containing 24 acres, and Innisbofin, 27. An abbey built on this island by a nephew of St. Patrick was plundered by the Danes in 1089. Lough Glinn forms a small portion of the same boundary towards Longford ; LoughsSheelin and Kinale are on its north-western limit towards Cavan : the white lake, Lough Deel, and Lough Bawn are small boundary lakes on the side of Meath. The water of the last-named of these has the peculiarity of being lower and more limpid in winter than in summer, being highest in June and lowest at Christmas : in summer its colour is green, like sea-water ; but in winter it is as pellucid as crystal and remarkably light.

Throughout the eastern part of the county the soil is a heavy loam from seven to twelve inches deep, resting on a yellow till : the land here is chiefly under pasture and feeds the fattest bullocks ; from its great fertility it has been called the “garden of Ireland;” the northern part is hilly and very fertile, extremely well adapted for sheepwalks, but chiefly applied to the grazing of black cattle. The barony of Moygoish is fertile, except towards the north, where there is much bog and marshy land. The central barony of Moyashel and Magheradernan is mostly composed of escars, ‘chiefly formed of calcareous sand and gravel. In the western baronies the country is generalhy flat and the soil light: the bog of Allen spreads over a large portion of the baronies of Brawney and Clonlonan. The farms are generalhy large; the chief crops, oats and potatoes, with some wheat, barley, flax, rape and clover. The resident gentry and large farmers have adopted the system of green crops; the most improved implements are in general use. Oxen, yoked in teams of two pairs, are frequently used in ploughing ; limestone gravel is preferred to any other substance as manure ; lime, either separatehy or in a compost with turf mould and the refuse of the farm-yard, is also used. The fences are bad and much neglected, except in the neighbourhood of demesnes and towinlands. The valleys throw up an abundance of rich grass, the hay of which, however, is much injured in consequence of not being cut till a late period, sometimes in September, and being suffered when made up to stand in the fields until the autumnal rains, by which the surface is injured, the lower part of the cocks spoiled, and in low situations the whole is liable to be carried away by the floods. Though dairy husbandry is not practised as extensively as the fertility of the soil would warrant, great quantities of butter are made of very superior quality, and always command a high price; it is chiefly sent to Dublin for the British markets. Much attention is paid to the breed of every kind of cattle. The long-horned cows are highly prized, as growing to a very large size and giving great quantities of milk; the oxen fatten very quickly, and the flavour of their beef is excellent. Sheep, for which several parts are well adapted, are not a favourite stock. Westmeath produces superior horses; the principal fair for their sale is at Mullingar; great numbers are also brought from Connaught , and reared here for sale in Dublin and in the English towns. Timber formerly abounded ; but the profuse use of it when plentiful, the great demand for charcoal for the old iron-works, and the neglect of any prospective measures to supply the deficiency thus arising, have rendered it scarce. The county has, nevertheless, some small copses andunderwoods, the remains of the ancient forests. Many trunks of large timber trees, particularly juniper, yew, and fir, have been found in the bogs; the wood, when dried, is always black. The waste and neglect of past ages is now being remedied; there are many thriving young plantations; several of the hills are clothed with wood; the ash grows in such abundance in hedge rows as to prove it to be indigenous to the soil ; hazel is encouraged, in order to make hoops for butter-firkins ; Scotch firs thrive on boggy bottoms, and larch still better.

The county is wholly included within the great limestone plain of Ireland, of which it forms the most elevated portion. The uniformity of its geological structure is broken only at Moate andBallymahon, in each of which places an isolated protuberant mass of sandstone rises from beneath the general substratum. The predominating colour of the limestone is a blueish grey of various degrees of intensity; it is often tinged with black and sometimes passes into deep black, particularly in those parts in which it is interstratifed with beds of clay-slate, calp orswinestone, or where it abounds with lydian stone. The black limestone in the latter case is a hard compact rock, requiring much fuel for burning it, and is by no means serviceable for agricultural purposes. The structure of the limestone varies from the perfectly compact to the conjointly compact and foliated, and even to the granularly foliated: beds of the last kind are quarried and wrought for various purposes in the northern baronies. Copper, lead, coal, and yellow and dove-coloured marble have been found in small quantities, but not so as to induce searches for the parent bed. A pair of elk’s horns, found in a bog, were presented to Charles I. shortly before the commencement of the civil war ; stags’ horns in a state of great decomposition have been found near the shores of Lough Iron.

The manufactures are merely such as supply the demands of the inhabitants, being confined almost wholly to friezes, flannels, and coarse linens. There are no fisheries of any consequence, although all the lakes are stored with fish of various kinds and excellent quality. The Inny is well stocked with bream, trout, pike, eel, and roach ; salmon is found only in the luny and Brosna, coming out of the Shannon ; Lough Dereveragh is celebrated for its white and red trout ; and about the month of May a small fish of a very pleasant flavour, called the Goaske, of the size of a herring, is taken in this and the neighbouring lake. In the ditches near the borders of LoughHoyle an incredible quantity of the fry of fish is caught from September to March. In the bogs, and especially in slimy pits covered with water, is found a muscle, flatter and broader than the common sea muscle, the shell brighter in colour, much thinner, and very brittle. They are not numerous, nor are they much used as food.

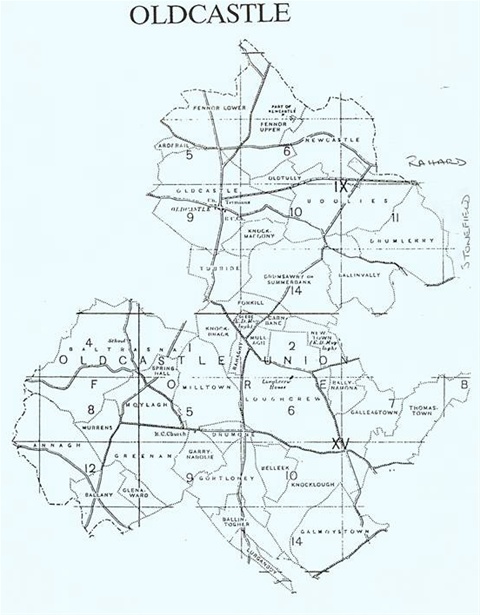

The Brosna and the Inny are the only rivers of any importance in the county : the former rises near Lough Hoyle ; the latter at Loughcrew, in the county of Meath . Numerous rivulets, flowing through every part, discharge themselves either into one of the lakes, or of the larger rivers. The more remarkable of the lesser rivers are the Mongagh, the Glore, the Gaine, and theRathconrath. The Shannon forms the western boundary from Lough Ree to a point some miles south of Athlone. The Royal Canal enters the county from that of Meath, two miles north ofKinnegad, and after crossing the Inny by an aqueduct, enters the county of Longford nearTinellick. A branch of the Grand Canal enters from the King’s county near Rahue, and proceeds to Kilbeggan. The roads are numerous through every part ; those of modern construction are well laid out and maintained ; the older are ill laid out and constructed, but these defects are in progress of being remedied.

Many vestiges of very remote antiquity may be traced in the neighbourhood of Ballintubber, and others of a similar description are observable in Moycashel. Of the numerous monastic institutions scattered through the county, those of Clonfad, Kilconiry, Drumcree, Forgney,Killuken, Leckin, Lynn, and Rathugh still remain, either wholly or in part, as places of worship either of Protestants or Roman Catholics. The ruins of those of Farranemanagh, Fore,Kilbeggan, Kilmocahill, and Multifarnham are still in existence: those of Tristernagh and of the houses of the Franciscans, Dominicans, and Augustinians of Mullingar are utterly destroyed ;Athlone had a house of Conventual Franciscans : the existence of several others is now ascertained only by the names of the places in which they flourished.

The ruins of ancient castles, several of which were erected by Hugh de Lacy, are numerous : the remains of Kilbixy castle, his chief residence, though now obliterated, were extensive in the year 1680. Those of Ardnorcher, or Horseleap, another of de Lacy’s castles, and the place where he met with a violent death from the hands of one of his own dependents, are still visible. Rathwire, Sonnagh, and Killare were also built by de Lacy : the second of these stands on the verge of a small but beautiful lake ; the third afterwards fell into the hands of the MacGeoghegans, the mansion of which family was at Castle Geoghegan, and some remains of it are still visible. Other remarkable castles were Delvin, the seat of the Nugents ; Leney, belonging to the Gaynors ; Empor, to the Daltons ; Killaniny and Ardnagrath, to the Dillons ; Bracca, nearArdnorcher, to the Handys, who have a modern mansion in its neighbourhood ; and Clare Castle, or Mullaghcloe, the headquarters of Generals de Ginkell and Douglas when preparing for the siege of Ballymore. Several castles of the Mac Geoghegans were in the neighbourhoodof Kilbeggan. The modern mansions of the nobility and gentry are noticed under the heads of their respective parishes.

The peasants are a healthy robust race. The women retain their maiden name after marriage; they perform the outdoor work, bring the turf home in carts, and share in the labours of the field. The English language is everywhere spoken, except by some of the old people, and that only in ordinary conversa-tion among themselves. The habitations are poor; the roofs without ceilings, formed of a few couples, and supported by two or three props, over which the boughs of trees not stripped of their leaves are laid crossways, and these are covered with turf and thatched with straw. A hole in the roof gives vent to the smoke; and the bare ground constitutes the floor and hearth. The house-leek is encouraged to grow on the thatch, from a notion that it is a preservative against fire : the peasants make their horses swim in some of the lakes on Garlick Sunday, the second Sunday in August, to preserve them in health during the remainder of the year. There is a chalybeate spa at Grangemore, near Killucan ; but the water is little used, in consequence of the difficulty of access to the place. Westmeath gives the title of Marquess to the family of Nugent.

Co. Westmeath County

Published in The History of Parliament: the House of Commons 1820-1832, ed. D.R. Fisher, 2009

Available from Cambridge University Press

Number of registered freeholders:

2,601 in 1829; 641 in 1830

Number of voters:

2,507

in 18261

Elections

| Date | Candidate |

Votes |

| 18 Mar. 1820 |

| |

|

|

| |

| 5 Mar. 1824 | ROBERT SMYTH vice Rochfort, deceased |

|

| 22 June 1826 | 1419 | |

|

| 1241 | |

|

| 1217 | |

|

| Richard Malone | 541 |

| 12 Aug. 1830 | 353 | |

|

| 336 | |

|

|

198 | |

|

| Gerald Dease | 86 |

|

9 May 1831 |

| |

|

|

|

Main Article

Westmeath was predominantly arable, producing mainly oats and potatoes. There were several market towns, including Castle Pollard, Moate andRathowen, the disfranchised boroughs of Fore, Kilbeggan and Mullingar, the venue for county elections, and the parliamentary borough of Athlone, which lay partly in Roscommon.2The representation had long been dominated by the childless George Rochfort, 2nd earl of Belvidere, whose kinsmanGustavus Hume Rochfort had sat since 1798. Following Belvidere’s death in 1814 and the breakup of his estates, however, the commanding interest had passed to Thomas Pakenham, 2nd earl of Longford, of Pakenham Hall, Castle Pollard. His brother Hercules had in 1808 replaced William Smyth, the nominee of the ailing Nugent interest headed by George Frederick Nugent, 7th earl of Westmeath. Unsuccessful attempts to unseat the sitting Members had been mounted by Westmeath’s heir Lord Delvin and Robert Stearne Tighe of Michelstown, both of whom had solicited the support of William Handcock, 1st Baron Castlemaine, the proprietor of Athlone, Sir Thomas Chapman of Killua, the various branches of the Smyth family and a growing ‘Catholic interest’.3

At the 1820 general election Rochfort and Pakenham offered again. Tighe urged the electors to ‘change your representatives’ and insist that they ‘give some pledge for the future’, as ‘Ireland is neither prosperous or safe’, but declined to stand himself. There was no opposition.4 Both Members continued to support the Liverpool ministry. Only Pakenham attended to oppose Catholic claims in 1821, but Rochfort paired against the bill to relieve Catholic peers of their disabilities the following year. On Rochfort’s death in 1824 his son and heir Gustavus, with only a modest inheritance, refused to come forward, despite the solicitations of ‘numerous friends’. Robert Smyth of Drumcree, only son of William Smyth, offered, citing ‘nearly similar’ political principles to those of his father and refusing to be ‘bound by any pledges’. He was supported by Longford, Richard Malone of Baronston, his proposer, and Chapman, who apparently looked on him as ‘a sort of locum tenens’ until his son Montagu came of age. Hugh Morgan Tuite of Sonna, the pro-Catholic son of a resident gentleman of ‘about £5,000 per annum’, made a ‘limited canvass’, but on finding ‘the strong interests combined’ against him withdrew, hinting that he intended to stand at the next general election. Richard Levinge of Knockdrim Castle was also spoken of and obtained ‘numerous assurances of support’, but he declined from ‘circumstances of a private nature’, requesting that his friends ‘keep themselves disengaged for any future election’. Smyth, who claimed to be ‘truly independent’, was returned unopposed. At the chairing he scattered a large bag of silver.5 He opposed Catholic claims, to which Pakenham became a convert in 1825, much to the dismay of Longford. During the rumours of a dissolution that September it was reported to Peel, the home secretary, that the ‘Westmeath Protestant gentlemen’ were ‘outraged with Pakenham for his votes’ on the issue.6 The following month the grand jury met at Moate to condemn the ‘outrages’ that had followed the rejection of the Catholic relief bill and call on the magistrates for ‘stronger punishments’.7

At the 1826 general election Pakenham retired amidst reports, which he repudiated, that he had been ‘discarded’ by his brother and the ‘high Protestant interest’. Smyth stood again, denying allegations in the Catholic press, which pilloried him as ‘the most stupid and silly man in the county’, that he was ‘a person advocating violent political opinions’. Gustavus Rochfort, whose family had ‘long abandoned their influence’, came forward on the ‘Purple [Longford] and Orange interest’, citing his father’s services. A series of placards, allegedly produced by the Catholic Association, charged him with being ‘put forward by an intolerant and bigoted faction, who if they could, would exterminate you and every other Catholic off the face of the earth’, and denounced him and Smyth as ‘two puppets in the hands of the Orange faction’ and ‘the sworn enemies of you and your religion’. Tuite declared on the Catholic interest, stating his independence from ‘any particular line of politics’ and his belief that emancipation would restore tranquillity. He urged his supporters, who included Malone, Sir Richard Nagle of Jamestown and Longford’s uncle, Admiral Sir Thomas Pakenham, to ‘abstain from a violent and inflammatory course’. The Irish under-secretary Gregory informed Peel that the ‘Popish priests are endeavouring to detach the tenants from their Protestant landlords in Westmeath to support Tuite, but they are not expected to succeed’.8 During the ensuing contest over 100 people were wounded and two men killed in ‘scenes that would disgrace the inhabitants of New Zealand’. Smyth was proposed by Chapman, Rochfort by RichardHandcock* and Tuite, who arrived in a ‘caravan drawn by a motley crew of the sans culottes armed with bludgeons’, by Malone. On the first day it became clear that the ‘real struggle’ would be between Smyth and Tuite, whereupon Malone was ‘started as a fourth candidate by the liberal party’. (The Catholic freeholders had initially been advised to give their second votes to Smyth, on the grounds that it was ‘better to have an idiot than an Orangeman’ returned.) During the second day, at the close of which Rochfort had secured 681 votes, Smyth 577, Tuite 494 and Malone an unspecified number, the Catholic priests were reported to have been ‘very busy about the booths, threatening, persuading and noting down such as voted contrary to their wishes’, whom they advised to ‘prepare their coffins or leave the country’. For the next six days polling was repeatedly interrupted by disturbances and on the seventh a troop of cavalry was sent to disperse the rioters. One of the agents recorded ‘great complaints about locking up voters, stopping them on the roads, beating and swearing them to vote for the priests’ friends, closing booths, etc.’, and that ‘it don’t seem a gentlemanly contest’. Rochfort and Tuite were returned on the eighth day, when Smyth, who was only 24 votes behind, objected to the closure of the poll. Smyth absented himself from the declaration, leaving his kinsman Henry Smyth to denounce the ‘unconstitutional’ interference of the priests who had ‘prostituted their altars’ for Tuite, and to promise to challenge the return. Tuite denied that the contest had been ‘carried on riotously’ and praised the ‘good temper and orderly conduct’ of his supporters before dispensing silver from the chair, which Rochfort declined to do. A mob later went on the rampage, chanting ‘Come out, you bloody Orangemen’, and, ‘We have not forgotten ‘98 yet’.9 The contest was one of those later described by the Whig James Abercromby* as ‘a sort of little bloodless revolution’, in which ‘the political power of the state has passed from the landed aristocracy’ into ‘the hands of the Catholic priests, the natural enemies of the government’; the ‘alliance of gentry in favour of Lord Longford was so great that he looked with scorn on Tuite’, who ‘with the evil of the priests triumphed’.10

Smyth’s petition, alleging that his supporters had been kidnapped by mobs, threatened with ‘excommunication’ by the priests and had their ‘affidavits of registry’ unfairly rejected, and that the poll had been ‘illegally terminated early’, was presented on 22 Nov. 1826. Citing the admission of 12 Catholic freeholders with ‘estates for the life of one Peyton John Gamble, who had died three months before’, he complained of ‘gross impartiality’ in the issuing of affidavits by Jonathon Ardill, a clerk of the peace, whose nephew Thomas had been retained by Tuite. If the 50 freeholders ‘improperly allowed were taken off the pollbooks’, he contended, he would have a majority.11 The petition lapsed, 11 Dec., but one in similar terms from Smyth’s supporters, who included his kinsman Ralph Smyth of Gaybrook, William Fetherston of Carrick and Tighe, was presented, 4 Dec. 1826. Petitions complaining of an insufficient Member’s property qualification were presented against Rochfort, 27 Nov., and Tuite, 8 Dec., 1826, but lapsed, 12 Dec. 1826 and 8 Feb. 1827 respectively.12 On 14 Feb. 1827 Tuite unexpectedly announced that he would not defend his return, but Nagle, Malone and others successfully petitioned to be admitted as parties for his defence, 8 Mar. 1827. A commission of inquiry was appointed, 29 Mar., but it disintegrated the following year, whereupon a committee was appointed, 18 Apr., which ruled in Tuite’s favour, 28 Apr. 1828.13

Rochfort opposed and Tuite supported Catholic relief, against which petitions condemning the Association and the ‘undisguised interference of the priesthood’ in the late election were presented to the Commons, 12 Feb., 2 Mar. 1827. Favourable ones reached the Commons, 26 Mar. 1827, 18 Feb., 2 May 1828, and the Lords, 6 Mar. 1827.14 One against alteration of the corn laws was presented to the Lords, 11 June 1827.15 Following appeals by the Westmeath Journal, a Brunswick Club, whose vice-presidents included Gustavus Lambart of Beau Parc, Fetherston and Rochfort, a founder member of the Brunswick Constitutional Club of Ireland, was established at Tyrrellpass, 27 Oct. 1828. Longford and the Handcock were toasted at an Orange celebration at Moate, 4 Nov. That month Longford provided the duke of Wellington, the premier, with ‘a cypher’ used by the Jesuits, but added that the language employed at Catholic meetings ‘tells more ... than any cypher can indicate’.16 On 25 Nov. 1828 the Westmeath Brunswick Club held its inaugural meeting at Mullingar, attended by Longford, Fetherston, Henry Smyth and Rochfort, when a petition against Catholic claims was started.17 Tuite was a convenor for the meeting of the ‘friends of civil and religious liberty’ at the Rotunda, Dublin, 20 Jan. 1829.18 He andRochfort took opposite sides on the Wellington ministry’s concession of emancipation, for which petitions were presented to the Commons, 17 Feb., 3, 10 Mar. 1829. Hostile ones reached the Commons, 3 Mar., and the Lords, 27 Mar.19 By the accompanying alteration of the franchise the registered electorate was reduced from 2,601 to 641, of whom 170 qualified at the new minimum freehold of £10, 125 at £20 and 346 at £50.20 Nagle was a member of the committee established for the O’Connell testimonial, 25 Mar.21 Petitions were presented to the Lords for repeal of the Irish Subletting Act, 12 Feb., and to the Commons for the introduction of an Irish poor law, 28 May.22 In November 1829 Viscount Forbes, Member for countyLongford, informed Lord Anglesey, the former viceroy, that Westmeath was in a ‘disturbed’ state.23

At the 1830 general election Rochfort offered again. He was joined by Tuite, who cited his opposition to increased taxation and infringements on the ‘liberty of the press’. Smyth was spoken of but declined, and Montagu Chapman, recently of age, declared on the combined interest of his father andLongford, who were said to have formed a ‘complete coalition’ for the ‘purpose of ousting Tuite, whose triumph over them in 1826 will never be forgiven’. Nicholas Fitzsimon of Broughall Castle, King’s County, was rumoured but declined a requisition from the Catholics, who at the last minute put up Gerald Dease of Turbotston, nephew of the 8th earl of Fingall and cousin of Lord Killeen, Member for county Meath. An observer in Mullingar reported that ‘there promises to be a wicked contest here’ and that ‘the priests are already interfering in a most unconstitutional manner’.24 At the nomination Rochfort was proposed by Handcock, Tuite by Nagle and Chapman by William Dutton Pollard of Castle Pollard. At the end of the first dayRochfort had 238 votes, Chapman 223, Tuite 147, and Dease 61. Next day Tuite, noting that he had been ‘rather remiss’ in his canvass, and Deaseretired. It was later claimed that ‘but for the frivolous objections’ lodged by the Catholics ‘for the purpose of delay, upwards of nearly 200 more votes would have been polled in their favour’.25 Westmeath was erroneously listed as a ‘gain’ by the Wellington ministry, which both Members helped to vote out of office. The Grey ministry’s reform bill was supported by Chapman, but opposed by Rochfort.

At the 1831 general election Rochfort, who had been reconciled to the Tories, stood firm, ‘sufficient’ party funds having been placed at his disposal.26 Chapman offered as an ‘uncompromising’ supporter of reform, over which many of his former supporters, including the anti-ToryBrunswickers, were reported to be ‘deeply divided’. Sensing an opening, a number of candidates declared and another ‘severe contest’ was expected. Tuite started but withdrew, whereupon Percy Fitzgerald Nugent of Donmore, the head of ‘a respectable Catholic family’, came forward professing support for ‘peace, economy and reform’. Smyth offered, promising to resume his previous line of conduct. Levinge, who was last spoken of in 1824, also came forward in response to a requisition from the ‘independent’ interest. The return of Rochfort was deemed certain by the Protestant press, which contended that ‘plumpers will be given to him in the event of a contest, even by the personal friends and the relations of his colleague’. In the event, however, Nugent, Levinge and Smyth agreed to retire at the nomination (the latter after some persuasion), ‘in order to prevent the county being disturbed’. Rochfort, who was reported to have ‘undergone a change’ and given a ‘sort of pledge’ for reform, and Chapman were returned unopposed.27 Rochfort continued to oppose and Chapman to support reform. Petitions reached the Lords condemning the reform bill as ‘short-sighted’ and ‘erected upon the shifting foundation of popular clamour’, 15 July 1831, and one in favour, 20 Feb. 1832.28 That month Chapman attended a county meeting to vote a petition for an Irish measure ‘as effective and comprehensive’ as the English one, which he presented, 9 Mar.29 Petitions were presented to the Commons against the Irish education plan, 26 Jan., and for the abolition of tithes, 9 Mar.30 Rochfort presented one from the magistrates and the newly appointed lord lieutenant, the marquess of Westmeath, complaining of the ‘defiance of the peasantry’ and for greater powers ‘to restrain insurgency’, 15 Mar. 1832.31 The Irish Reform Act did not add any leaseholders to the freeholders, who had increased to 1,395 (985 registered at £10, 140 at £20, and 270 at £50).32 Thereafter the Handcock and Longford interests retained ‘much weight at elections’, but ‘lost the predominance’.33Only 486 voters polled at the 1832 general election, when the Liberals Chapman and Nagle defeated the Conservatives Rochfort andGustavus Lambart.34 The county remained a Liberal stronghold until the advent of Home Rule.

Author: Philip Salmon

Notes

- 1.PP (1829), xxii. 22.

- 2.S. Lewis, Top. Dict. of Ireland (1837), ii. 695.

- 3.HP Commons, 1790-1820, ii. 696-7.

- 4.The Times, 17 Feb.; Dublin Evening Post, 2, 9, 14 Mar. 1820.

- 5.Westmeath Jnl. 12, 26 Feb., 11 Mar. 1824.

- 6.Add. 40381, f. 209.

- 7.Westmeath Jnl. 20 Oct. 1825.

- 8.Brougham mss, Abercromby to Brougham, 12 July; The Times, 27 May, 6 June; Westmeath Jnl. 8, 15, 22 June; Dublin Evening Post, 10, 17, 22 June 1826; Add. 40334, f. 171; CJ, lxxxii. 17.

- 9.Westmeath Jnl. 29 June, 6 July; Dublin Evening Post, 27 June 1826.

- 10.Brougham mss, Abercromby to Brougham, 12 July 1826.

- 11.Westmeath Jnl. 30 Nov. 1826; CJ, lxxxii. 16-17.

- 12.CJ, lxxxii. 32, 33, 56, 107, 111, 112, 126.

- 13.Ibid. 168, 293, 429; lxxxiii. 244, 277.

- 14.Ibid. lxxxii. 154, 254, 358; lxxxiii. 78, 304; LJ, lix. 136.

- 15.LJ, lix. 395.

- 16.Wellington mss WP1/966/3.

- 17.Westmeath Jnl. 28 Aug., 25 Sept., 2, 30 Oct., 13, 27 Nov., 4 Dec. 1828.

- 18.Dublin Evening Post, 8 Jan. 1829.

- 19.CJ, lxxxiv. 42, 98, 121; LJ, lxi. 302.

- 20.PP (1830), xxix. 462-3.

- 21.Dublin Evening Post, 26 Mar. 1829.

- 22.LJ, lxi. 29; CJ, lxxxiv. 349.

- 23.PRO NI, Anglesey mss D619/32/A/3/1/239.

- 24.Dublin Evening Post, 29 July, 3, 14 Aug. 1830; NLI, Farnham mss 18602 (40), Hodson to Maxwell, 9 Aug. 1830.

- 25.Dublin Evening Post, 12, 14 Aug.; Roscommon and Leitrim Gazette, 14 Aug. 1830.

- 26.Farnham mss 18606 (1), Arbuthnot to Farnham, 4 May 1831.

- 27.Dublin Evening Post, 3, 5, 12 May; O’Connell Corresp. iv. 1800; The Times, 13 May; Roscommon and Leitrim Gazette, 7, 14 May 1831.

- 28.LJ, lxiii. 821; lxiv. 62.

- 29.CJ, lxxxvii. 177.

- 30.Ibid. 52, 177-8.

- 31.Ibid. 196.

- 32.PP (1833), xxvii. 301.

- 33.Dod’s Electoral Facts ed. H.J. Hanham, 333.

- 34.PP (1833), xxvii. 301.

List of MPs elected in the United Kingdom general election, 1885

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| (1874) | |

| (1880) | |

| 23rd Parliament | (1885) |

| (1886) | |

| (1892) |

This is a list of Members of Parliament (MPs) elected to the 23rd Parliament of the United Kingdom at the 1885 general election, held over several days from 24 November 1885 to 18 December 1885.

| Irish Parliamentary |

County Meath (An Mhí, originally Mide, "the middle kingdom")

In the original Gaelic divisions Mide was in fact a fifth province and, as well as the present Co. Meath, incorporated what is now Westmeath and large parts of Cavan and Longford. It was reduced to its present size by the Normans in the thirteenth century; large parts of the territory had been granted to Hugh de Lacy, who built massive fortifications at Trim and elsewhere to enforce and protect his possession. Despite its proximity to Dublin, only part of the county remained in the Pale as English power waned in the late Middle Ages.

In 1549 Meath was split into Meath and Westmeath by the English.

12 Baronies of County Westmeath

All - O'Conallain (O'Connellan or O'Kendellan) were princes of Ui Laeghari or "Ive-Leary", an extensive territory in the counties of Meath & Westmeath. The O'Maolconrys (O'Conry) were chiefs of Teffia (or Westmeath) when they crossed the Shannon in the 10th century receiving lands from the O'Connor kings of Connacht. MacConmedha (MacConway) is cited as a principal chief of Teffia, in Muintir Laodagain. Teffia formed a greater portion of the ancient kingdom of Meath. In later times a large part of the county came to be referred as Dillon's country.

Brawny - The O'Breen were lords of Breaghmaine, a former name for Brawny. The O'Malone sept had large territory here, and were known as barons of Clan Malone and barons Sunderlin.

Clonlonan - The Sinnach (later Fox) O'Catharniagh family were chiefs in this territory which also included Rathconlan and the barony of Kilkcourcy in Co. Offaly. They were named for Catharniagh, the head prince ofTeffia, and the O'Kearneys were of this clan. Anciently, the Mac Auleys were chiefs of Calraidhean-Chala in the parish of Ballyloughloe. The O Daliagh (O'Daly) sept is cited as chiefs of Teffia with territory here. Septsnoted here in the 12th century included Ua Cairbre (O'Carbury) of Tuath Buada and Ua Braoin (O'Breen) of Conmaicne.

Corkaree - O'Hindradhain (O'Hanrahan) are given as chiefs of Corcaraidhe or Corco Roíde, from which the name of the barony derives.

Delvin - In the 8th century this area is cited as Delbna Mór. O'Fionnalain (Fenelon) are cited as lords of Delvin prior to the arrival of the Normans. Sir Gilbert De Nogent became baron here after the Norman Invasion, and the Nugent family were Barons of Delvin.

Farbill - The territory of Fir Bile is noted here in the 8th century. The Ua hAinbheith (O'Hanfey) sept is noted here in the 12th century.

Fartullagh - O'Dubhlaich (O'Dooley), chiefs and lords of Fertullach (Fir Tulach) up to the 12th century, subsequently forced by the O'Melaghlins and the Tyrrells into the barony of Ballybritt in Co. Offaly.

Fore - The Ua Maoil Tuile (MacTullys) are noted here as evidenced by the name of Tullystown, anciently included as part of Uí Maic Uais Mide. Ua Maoil Challan (Mulholland) of Delbna Bec is cited here in the 12th century.

Kilkenny West - The territory of Conmaicne Bec is noted here very early. The O'Tolairg (O'Toler) name is cited as chief of Quirene, a former name of this barony.

Moycashel - The Mag Eochagain (MacGeoghegan) sept were chiefs of Cinel Fiacha or Cenél Fiachach (Kinalea) who were centered here, as well as parts of Rathconrath and Fartullagh. The Cenél nÉnna septs of UaBraonain (O'Brennan) of Creeve and Mac Ruairc (Mac Rourke) of Teallach-Conmasa were noted here in the 12th century.

Moyashel & Magheradernon - The O'Dalaigh (O'Daly) clan of Corco Adaim was anciently centered in the barony of Magheradernon. Ua Donnchadha (O'Donoghue) of Tellach Modharain is noted here in the 12th century. The Norman family of Tuite is given as barons of Moyashel after the 12th century.

Moygoish - MacEvoy was chief here in a territory called Ui Mac Uas. O'Hennesy, chief of Ui Mac Uas, ruled after the MacEvoys. An O'Curry family is also cited as chiefs here. The O'Harts (Ua hAirt), a sept of Síl nÁedoSláine, were noted here in the 12th century.

Rathconrath - Mac Aodha (MacGee) of Muintir Tlámáin is noted here and in Moyashel in the 12th century. It was later referred to as Dalton's country, the Norman family of Dalton were Lords of Rathconrath following the 12th century. A Donegan sept is cited here in the 17th century.

Misc - O'Convally are found alongside Quinn, O'Kearney and O'Loughnan as principal chiefs in Teffia. O'Scoladihe (O'Scully) is found anciently centered in Co. Westmeath until the Norman invasion. The O'Shaughlinfamily is noted here in the parish of Dysart. Mac Carrgamhna (Mac Caron or Gaffney) of Muintir Mailsinna as well as Mac Con Meadha (MacConway) of Muintir Laoghachain are noted in west Co. Westmeath / south Co.Longford in the 12th century.

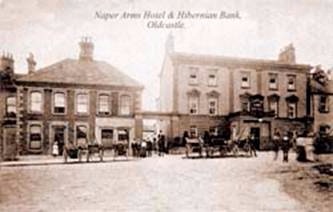

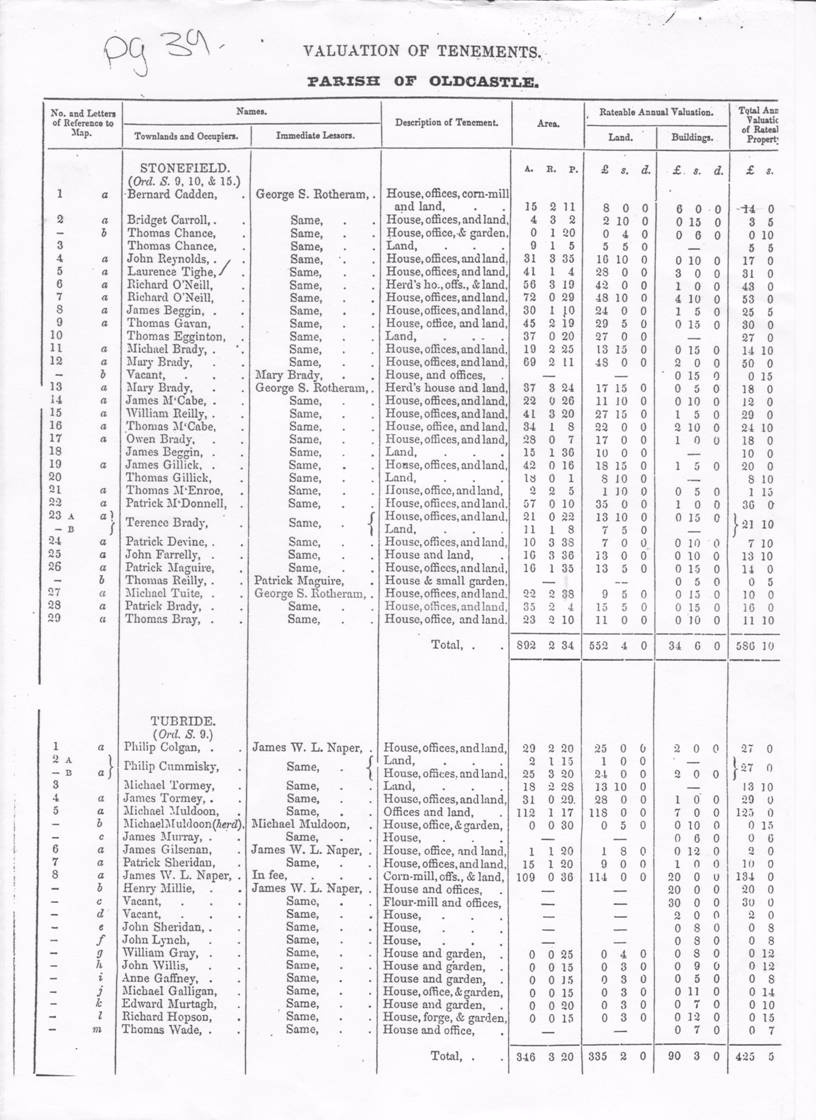

Naper House in Loughcrew

Naper House in Loughcrew

Owned by the Naper family who were the local Protestant landlords. As was common for the time they were not liked by the local Catholic community. Set under the shadow of Slieve naCallagh, with its prehistoric tumuli, Loughcrew is a superb demesne, incorporating the remains of the 17th century seat of the Napers and the Greek Revival portico of the C. R. Cockerel house of 1823, which was destroyed by fire in 1960. The family continued to occupy the wing and have restored the garden under the EU Great Gardens of Ireland programme. The rustic gate lodge is in separate ownership and has been empty for a number of years. It is a picturesque structure, with the ground floor comprising 3 rusticated piers supporting segmental arches and random coursed stone to the upper floors with central gable. Windows are of latticed design. Deterioration is starting to become obvious on the roof.

The houses creator, the eccentric early 19th century architect, Charles Robert Cockerell, designed the exterior to suit the environment and the interior to suit himself. As a result, upper floor levels have a mezzanine-like appearance, with window sills positioned below floor level rather than above.

When the couple first saw it, it was no more than a shell. Some walls certainly, but no roof, no ceilings, no floors and no window panes in what had once been the elegant conservatory of the 400 year old Naper family mansion. Throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries, this room was home to dozens of exotic plants, but after a devastating fire in 1964, it was reduced to a state of roofless dereliction, its only tenant a Massey Ferguson tractor. When Emily Naper took on the task of restoring it, the covered the nasty concrete floor with limestone slabs and covered the overhead yawning gap with a glass wood-framed roof. Today, this area combines several functions - family and guest conservatory dining area in summer, table tennis room for the children in winter and alternate entrance hall all year round. The unusual wall texture is accounted for by the traditional 1830s composition of horse hair, cow hair, plaster, ox blood and brick. The walls are adorned by bear and wild boar shot by Charles Naper's grandfather.